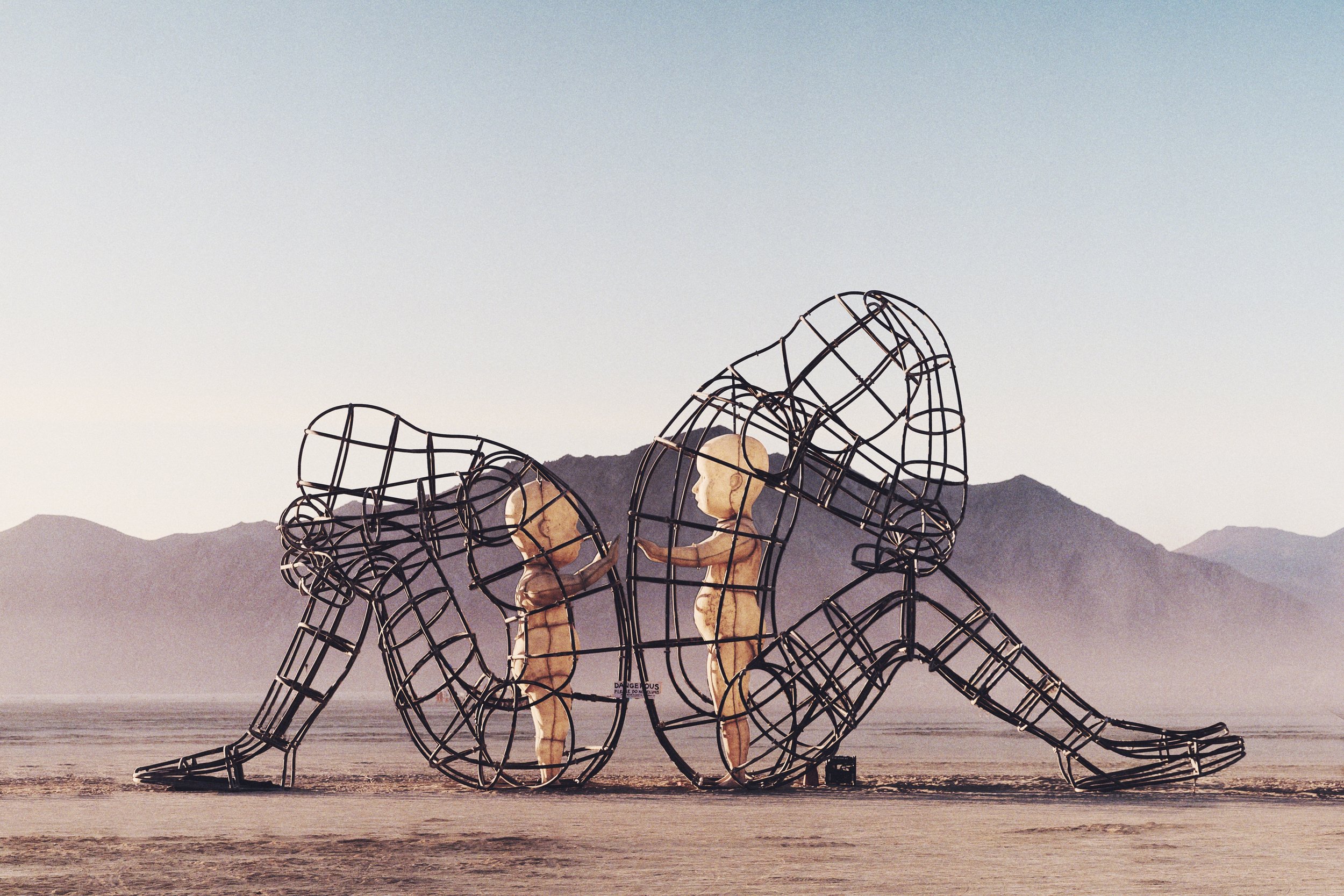

I panic when I don’t hear from them. I just want to be left alone. I want to reassure them that I’m here for them. These statements may capture several examples of responses from clients in your office engaging in work around their relationships. One powerful perspective on the functioning dynamics of intimate partner relationships is to look through the lens of attachment. In other words, by exploring childhood attachment and how it sets the foundation for interaction within relationships, we can experience an increased sense of awareness on how attachment translates to current relationships from needs being met or ignored in our early childhood experience.

Bonding Background

The study of attachment can first be linked to Mary Ainsworth and John Bowlby in the 1970s. Mary Ainsworth devised the Strange Situation, an experiment that placed babies in a lab with their attachment figure/parent and observed reaction in the baby as a stranger entered the room, as well as each baby’s ability to be soothed when the parent left the room and later returned. Based on Ainsworth’s research findings, we were able to identify three types of attachment: secure, anxious, and avoidant. Mary Main, another colleague, later identified a fourth type of attachment called disorganized to capture responses that were inconsistent and unpredictable when exploring a baby and their attachment figure.

Attachment Attributes

Secure attachment in childhood looks like a distressed infant that is easily comforted when the attachment figure engages them, such as picking them up and soothing them with soft voice, physical touch, and proximity. In adulthood, the secure attachment individual is highly desired for their ability to reassure their partner and present as calm, grounded, and confident in the relationship. Anxious attachment in children can be portrayed as significantly distressed when the parent exits the room, with increased difficulty to receive soothing or reassurance when the parent returns. In adult relationships, the anxious attachment individual’s anxiety prevents them from feeling reassured in the relationship and can drive their behaviors to present as needy, anxious, and sometimes paranoid that the relationship will fail or that they aren’t “good enough” for the relationship to work. Lastly, the avoidant attachment type in childhood will manifest in a baby as unaffected, cold, disconnected, and unconcerned with the parent leaving the room as well as an inclination to self-soothe, such as engaging in thumb sucking or playing with toys independently. The avoidant attached child has learned to rely only on themselves in not having the parent fully present, which can occur when parents are working long hours away from the child, are inconsistent in their reactions to soothe the child, or can occur in response to a parent’s mental illness such as depression preventing interaction and ability to attach in healthy ways. In adults, avoidant attachment continues the theme of self-sufficiency and “not needing anyone” in a relationship, preventing them from connecting at a deeper level with others and can be portrayed as reluctance to commit to a serious relationship.

Linking to Literature

With John Bowlby’s Attachment Theory in mind, Amir Levine wrote an insightful book called Attached, that explores intimate partner attachment more deeply and offers examples of adult behaviors that can provide insight or identification of attachment styles. For client use, there are also helpful YouTube videos that can provide a brief overview of adult attachment such as the one found here. Another author, Stan Tatkin, took the idea of attachment a step further by providing symbolic representation of attachment that can also help one identify their attachment style.

Secure Attachment: An Anchor

Anxious Attachment: A Wave

Avoidant Attachment: An Island

The imagery associated with attachment styles can help a client identify their reactions and resulting behaviors in intimate relationships, as well as assist them in identifying their partner’s attachment style and needs.

Creating Connection

In supporting your clients with exploring their attachment, you may find yourself pursuing additional training, such as Emotionally Focused Couples Therapy (EFT) that encourages vulnerable connection in couples and supports healing of attachment wounds. Or perhaps you link your attachment work to Gary Chapman’s The 5 Love Languages or communication and connection strategies from John Gottman’s training for couples’ work. Whatever means you choose to further dive into attachment needs, educating your clients on the possibility of positive shifts, such as moving to more secure attachment with their partners, can support movement towards healthier relationships. Levine and Tatkin emphasize that relationship attachment can shift and a person can present differently in each romantic relationship over their lifetime. With this in mind, exploring attachment can support your clients in discovering their own attachment styles as well as assist them in connecting and fostering healthy attachment in their intimate partner relationships.