As the year comes to a close, you may be looking to the new year to create resolution or revisit goals in the hope of change. It’s a time to explore goals that are measurable and attainable; it’s a time to create small steps to build self-confidence to remain motivated and hopeful. Perhaps you say “I want to join a gym to help my depression.” You want to work out every day to help your mood but aren’t currently working out on a consistent basis, and not at a gym. So, you find it important to explore your motivation as well as the perceived strengths and challenges of reaching your goal. You learn that smaller steps can support success and agree to working on short-term goals to build confidence and to move towards your long-term goal of working out daily.

Monitoring Motivation

Why is it important to explore motivation around a goal? Research tells us goals around fitness and gym attendance peak in January and dramatically decline by February and March every year. Additional research tells us that we must do something consistently for a minimum of 30 days for it to become a habit. What this conveys to us as human beings is that we need to see results or progress to continue to work hard at a goal. You may normalize this for yourself in understanding the pattern of motivation. You may also explore research on the Stages of Change from Motivational Interviewing as a visual to support yourself in identifying strengths and barriers to change. By being open and honest with yourself, you will be setting yourself up for success. Ask yourself the following questions to fully discover where your motivation lies (and note the Stages of Change in parentheses):

What do you want to change? (Precontemplation to Contemplation)

What makes that a problem for you? (Contemplation)

Is it a big enough problem to want something different? (Contemplation)

How would you achieve the desired change? (Preparation)

What do you need to support change? (Preparation)

What would help you to begin? (Action)

How will you know when you are ready for change? (Action)

What would help you keep going? (Maintenance)

Who/What would hold you accountable?

What would happen if you don’t succeed?

By exploring these questions, you can identify any current strengths or barriers to succeeding and further explore what is needed to progress through the Stages of Change.

Make it Measurable

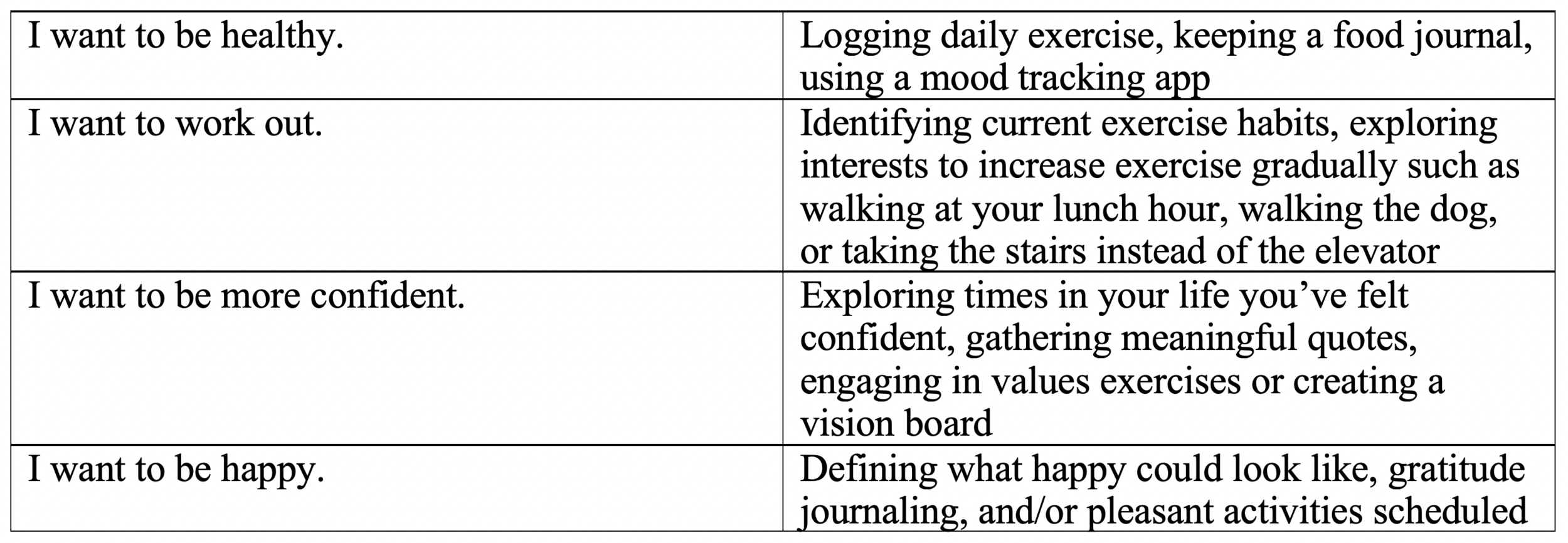

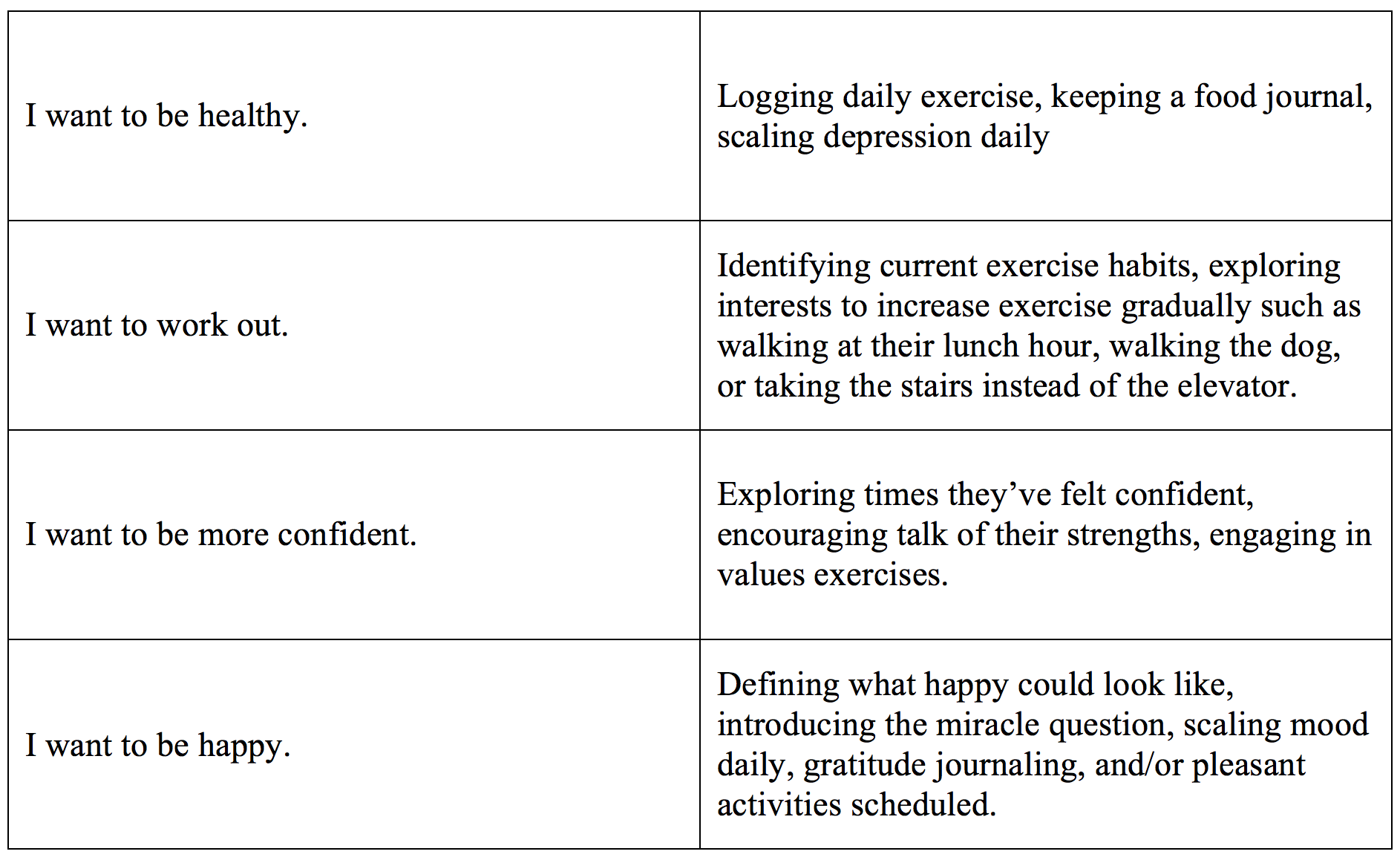

It isn’t uncommon for someone to identify a goal but not know how to attain it, thus remaining in the stage of contemplation. It becomes our responsibility to break down a long-term or larger goal into measurable, smaller pieces for it to feel worthwhile. Here are some examples of how to make it measurable when identifying a larger, more abstract goal:

Smaller, more measurable efforts can support short-term goals blending into long-term goals over time. By identifying and writing down goals that are measurable, can be reviewed regularly, and can be celebrated when attained, the effort it takes to achieve these goals can feel validated and encourage motivation for the long-term work as well.

Accountability Buddy

Motivation can be internal such as, “I can do this” or external, “she said I can do this.” Identifying a trusted support as an Accountability Buddy can help you achieve your goals. Accountability Buddies are selected as a support person who is aware of your goals and holds you accountable by remaining in regular contact with you on your progress. They may meet with you weekly, monthly or on whatever schedule can help you remain focused and present on the goals you are working towards. Sometimes Accountability Buddies have a similar goal and may participate alongside you, such as going to the gym with you three times per week. Not having to work towards a goal alone can serve as an incentive in absorbing someone else’s positivity when you begin to question your own motivation. You may struggle to recognize the small but important shifts in progress and begin to question why you are working so hard for minimal results. Perhaps they help you recognize the smaller changes that have taken place when you feel the seeds of doubt are planted, thus preventing you from giving up on a goal that is supporting healthy change. By identifying an Accountability Buddy that is supportive throughout the process, you can experience motivation and recognize goal progression, allowing the ongoing growth and change you desire.

“Change will not come if we wait for some other person or some other time. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for. We are the change that we seek.” Barack Obama.