When doing a “goals list” exercise in therapy sessions, start by telling telling clients to DREAM BIG!

Formulating a goals list is different for every individual. Counselors can be interested not only in the goals people choose but also in their reaction to creating the list itself. Sometimes people say they can’t think of any goals, which is an informative statement. It sends an important message about the person’s sense of value in the world. When a therapy client makes this statement, he/she provides the counselor with incentive and direction. It is rewarding to watch clients who start out by saying they have no goals, or can’t think of any goals, only to end the session with a goals list to take away with them for future reference.

In developing this exercise, counselors can work with clients to tap into their resilience, a tool which is helpful when attempting to work through a personal or professional setback. Also, the hope is that by creating this goals list a client will be improving their positive self-esteem. Next is the hope that a client will utilize the goals list to open his/her mind to a positive outlook - a world where the glass might be half full as opposed to half empty. Even if the goals list is not ‘realistic’ in terms of real life, just the actual act of writing down any dream or thought or hope a client might have is an exercise for the mind and the spirit.

Some clients have no problem coming up with long and varied goals lists. For them, the challenge is the move toward action in achieving the goals on their lists. In other instances, however, clients say they can’t think of goals because they believe they are not “allowed” to have goals for themselves. For whatever reason, throughout their lives, these clients were “programmed” not to consider their own individual thoughts, feelings, hopes, plans and dreams. Resistance is high with these clients, and asking them to think of goals for themselves stumps them, because it almost feels “wrong” for them to consider what THEY want.

There are other clients who come up with well planned and realistic goals, only to reject them because to follow these would somehow be “too good.” It’s as if they are so invested in the chaos of being “stuck” that even a glimmer of the possible is too scary, because then they have to give up a lifetime of investment in the chaotic lifestyles they have come to find “safe” or “comfortable” which is really code for “familiar” or “known.” Again, this gives the counselor clues in terms of directions forward therapeutically, in that the counselor is faced with massive resistance to change, even though the client talks the game of wanting change - a typical paradox.

When formulating goals lists with clients, there are some guidelines. First and most important, the items on the lists are to be goals they want for themselves, not based on the others in their lives, and not based on what they think they are “supposed to” want as goals. For example, of course I’m not opposed to the “get married and have a family” goal or the “graduate from college” goal, if those are on someone’s list. However, that still seems like something someone else (society, our parents, peers, etc.) tells us we’re “supposed to” want or do.

In terms of considering goals, counselors can encourage people not to think in terms of “supposed to.” Also, there are no restrictions - money or time or age or marital status or children or aging parents - or any of the other “reasons” people will identify as obstacles preventing them from achieving their goals. For example, people with children don’t need to write down, “I want to see my kids grow up and be happy and successful.” Counselors can remind people who are parents that the goals lists are to be about nobody else but themselves. Also, there can be no time deadlines - the “by a certain age I have to make a certain amount of money,” kind of thinking. And regarding the the subject of money, there can’t be dictates from others about how much money is “enough,” or that earning some amount of money will imply success. Again, it’s about what the individual believes for him or herself, not what someone has “programmed” the person to believe about money or success.

As mentioned above, the point of this exercise is to help clients open their minds to the limitless possibilities of life. For some, this is a difficult concept because they believe life is about a certain way of doing things, usually whatever way they were taught to believe as they were growing up. Then the ideas they were taught were further reinforced by others in their peer group. After all, most people want to “fit in” or be the “same as.” To be different from, or be the rugged individual in the group is sometimes to feel isolated and outcast. However, at this stage, clients are in a counselor’s office because of trying to fit in or be like everyone else, and discovering the emotional problems that go along with those efforts. They come in with their resistance, their unwillingness to change, even as they are acknowledging that they want things to be different from how they have been in the past. A paradox to be sure.

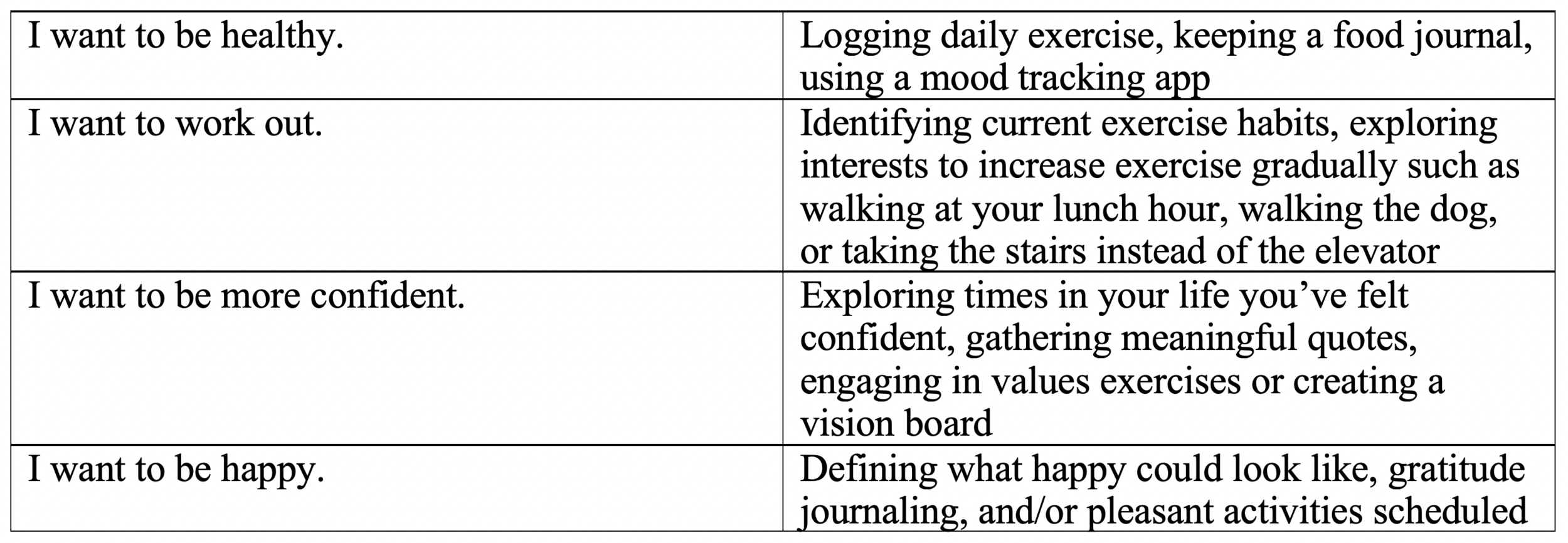

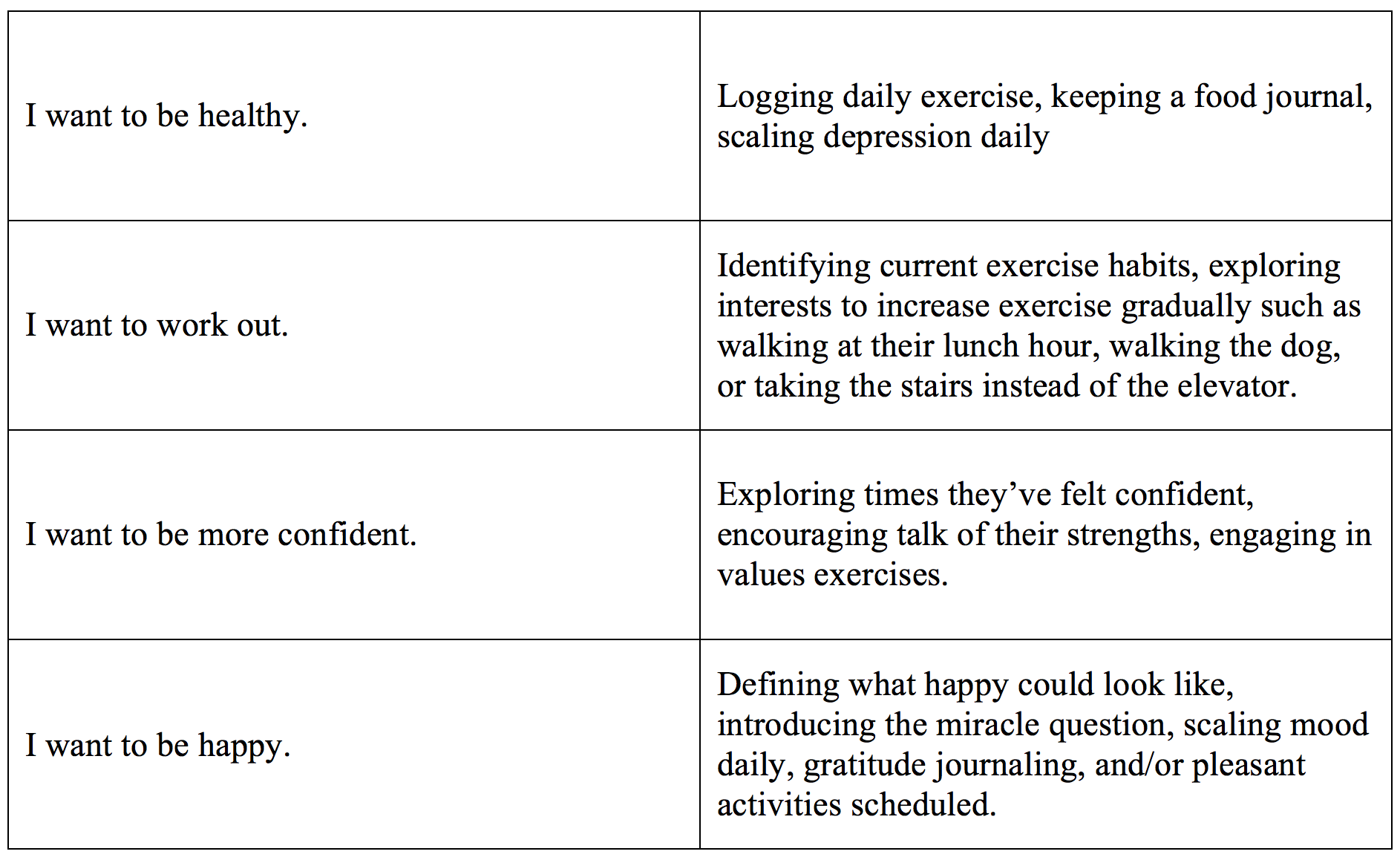

With the goals list, therefore, the counselor introduces the concept of all things possible, including the exercise of thinking about themselves in a selfish way. The counselor challenges clients to put their own needs first, to think in terms of their own personal priorities. The counselor encourages clients to define success as it relates to them personally, not in terms of money or possessions, but in terms of emotional well being. The role of the counselor is to provide a brainstorming conversation with the client in which resistance may be addressed, because there may be resistance to even attempting a goals list. Sometimes clients ask why they even need to have goals. Just the fact that they choose the word ‘need’ answers the question, doesn’t it?

Once the guidelines are out there, counselors can again encourage people to dream big! Some folks have an understanding of how this is helpful, and they start to write down their goals - large and small, real or imagined, practical or impractical, perhaps possible, perhaps not. For others there are still difficulties around feeling compelled to “be practical” or using phrases like, “that could never happen.” Not everyone is able to envision right away what it feels like to be selfish in a good way, thinking of self not in terms of anyone else. For them, the counselor can encourage continued talking and thinking and imagining. Eventually, just about every client understands how this exercise is worthwhile, because it takes clients out of the problem place and into the possible place - never a bad thing, right?

Do you have a goals list? Try it for yourself, and then keep it and refer to it from time to time. For one thing it’s a chance to dream, always worth some head time and space. For another, isn’t

it satisfying to achieve what you strive for? And lastly, it keeps clients in touch with forward motion, with listening to and following their hearts and thinking from a self place. Remember, when clients learn to put themselves and what they need at the head of their lists, they have that much more to give to the others in their lives who are valuable to them. Learning to do that and then putting it into action is in itself an excellent goal. When this is achieved, so much else is able to be done, and clients will know what it is to live life in that possible place.