“A sound mind in a sound body is a short but full description of a happy state in this world. He that has these two has little more to wish for; and he that wants either of them will be little the better for anything else.”

- John Locke, Some Thoughts Concerning Educations

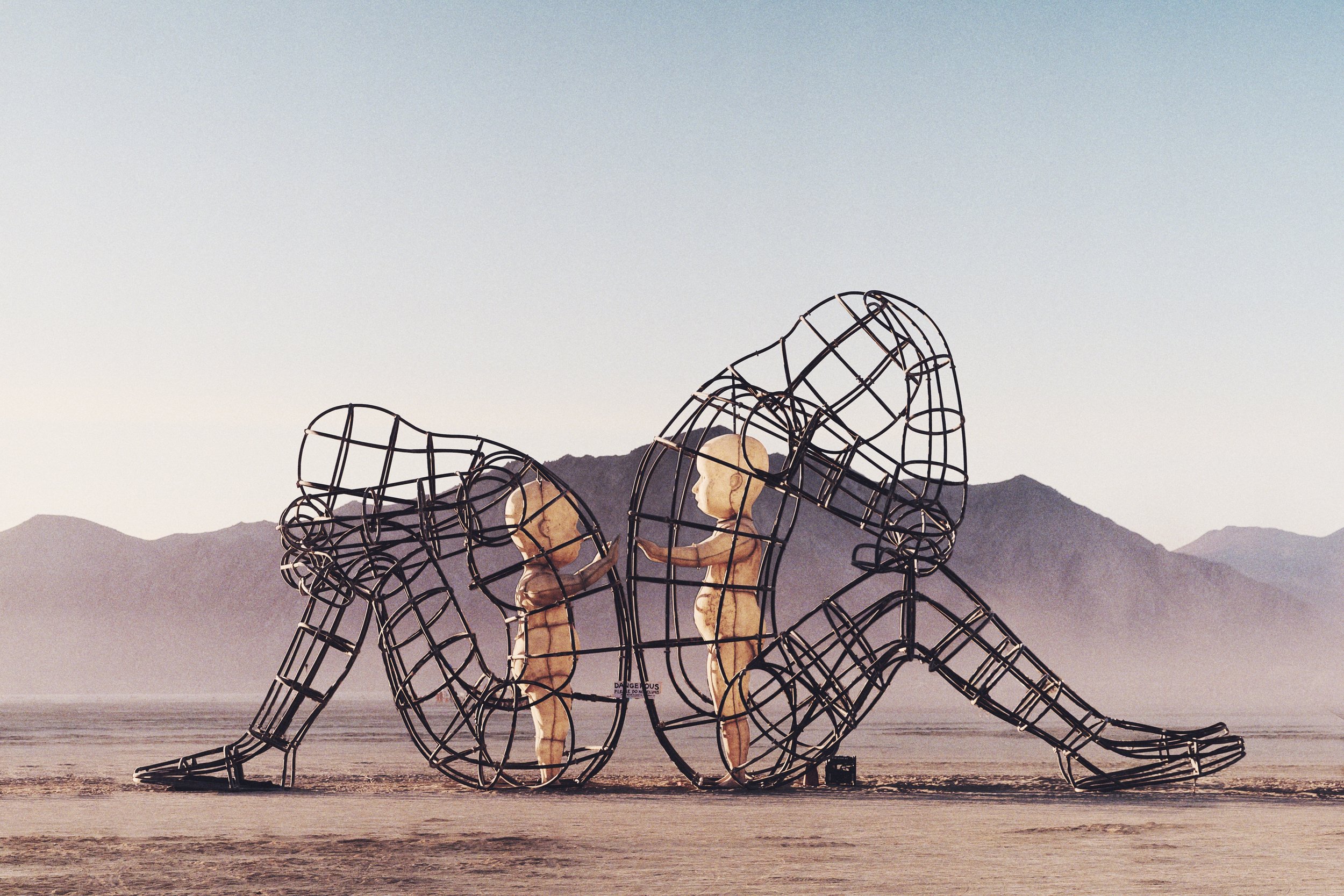

There is a profound connection between our bodies and minds. Despite our best efforts to help clients identify ways to increase their self-care, often getting a client to exercise on a regular basis is a tough sell. So, if you can’t get them to try going for a walk outside of session, why not try a Walk+Talk session?

We know that one of the best methods to increase self-care is exercise. Its positive impacts on our clients is well documented:

The effects of exercise have been shown to contribute to:

- maintaining good health (feeling better physically)

- weight loss or maintenance

- healthy physical function (aiding digestion and metabolism)

- increased strength, stamina, and muscle tone

- improved sleep

- increased energy

And while our clients likely know these benefits, they may not realize how beneficial exercise can be to their emotional wellbeing as well as their physical wellbeing.

Exercise has a positive impact on our emotional wellbeing by contributing to:

- powerful shifts of thought

- stress relief

- meditation

- a sense of calm

- an emotional release

- peacefulness

- mental and cognitive effects:

- cognitive clarity, a sense of control and a clearer head, self-esteem, optimism

Walk+Talk Therapy

One service I offer is Walk+Talk therapy, where we go for a walk during the client’s session. Walk+Talk sessions have been an effective way for busy moms and working professionals to fit in counseling (while eliminating the need for a babysitter for new parents).

Many people are drawn to it for convenience, but often Walk+Talk clients report that the movement during sessions has made them feel more comfortable, has aided in their memory, and helps them feel more creative and flexible in their problem solving.

If you’re a runner or do any type of exercise regularly, you’ve likely noticed the same phenomenon: we often feel our best and have our best ideas while on the move.

In “Working it Out - Using Exercise in Psychotherapy” by Kate F. Hays, he sums up this effect nicely:

“On long runs I seem to be able to pull together information in novel ways, by letting go of conscious linear thinking patterns. On the surface, these may appear as random thoughts, yet they end up coming together in delightful and meaningful ways. … The extraordinary part of this is that it is so effortless and perhaps that it happens at all. The kind of thinking that we spend years developing in graduate school is so taxing, time- consuming, linear. Perhaps Jung was correct after all. Rational, linear, conscious thinking takes effort and is not the way the brain naturally processes information. It is this dreamlike thinking—for lack of better descriptor—that is the way we usually process information. We’ve just learned to ignore and devalue it.”

The wonderful thing is, this dreamlike thinking, (otherwise known as a cognitive shift), that often leads to “ah-ha moments” and breakthroughs is available for the therapist and the client—leading to a productive session and further processing after a session.

Walk+Talk also lends itself to a plethora of therapeutic metaphors and symbolism regarding changes in thinking patterns, nonverbal communication, and empowerment.

Research on Walk+Talk Therapy

Despite this being a unique way to offer psychotherapy, there has been research that has supported its effectiveness:

- One researcher has consistently noted positive mood among active individuals and athletes. With exercise, negative moods (labeled as tension, depression, anger, fatigue, and confusion) diminish while positive mood states, such as vigor, increased.

- In a study comparing running with verbal therapy for the relief of depression, the researchers pointed out that “depressive cognitions and affect seldom emerge during running, and when they do, they are virtually impossible to maintain.

- Therapists who have used Walk+Talk have suggested markedly beneficial effects on mood, sense of well-being, and self-esteem (Hays, 1994, Jongsgard, 1989, Sime, 1996).

- Another researcher said, “even brisk walking seems to ‘loosen them up;’ they become less inhibited and constrained and more in touch with their immediate feelings and experience. He also observed that clients had more energy, were more aware of anger and assertive needs, talked about what they genuinely felt (in contrast to what they thought they should feel), and were more conscious of themselves yet less self-inhibited or self-conscious.

- In a study of the relationship between exercise and optimism, participants who engaged in aerobic or a combination of aerobic and anaerobic exercise experienced significantly lower levels of trait anxiety than those engaged only in anaerobic exercise.

- Another study found that acute vigorous physical activity among women accustomed to exercise was associated with significant improvements in affect and feeling states, particularly feelings of revitalization, positive affect, positive engagement, and tranquility. Measuring negative affect separately, they observed a statistically significant, although less powerful, decrease in negative affect.

- Jongsgard’s study showed:

- that exercise is a beneficial antidepressant both immediately and over the long term.

- although exercise decreased depression among all populations studied, it was most effective in decreasing depression for those most physically or psychologically unhealthy at the start of the exercise program

- regardless of gender, exercise was equally effective as an antidepressant

- the most frequent form of exercise used were walking and jogging

- the greater the length of the exercise program and the larger the total number of exercise sessions, the greater the decrease in depression with exercise

- the most effective antidepressant effect occurred with the combination of exercise and psychotherapy

- Jongsgard concluded, “the magnitude of change which results from exercise therapy by itself is as great as that associated with a variety of standard group and individual psychotherapies, some of which, in turn, have been shown to be as effective as antidepressant drug therapy” (p.135, “Working it Out”).

Exercise & Stress

Stress, something we all experience to varying degrees, involves heightened levels of both physiological and psychological arousal.

Thayer has developed a theory of mood that focuses on the dimensions and interactions of energy and tension. “Mood is assumed to be closely associated with central states of general bodily arousal with conscious components of energy (vs. tiredness) and tension (vs. calmness)”.

The most negative mood states are those combining both low energy and high tension.

Optimal levels, alternatively, are the result of activities that raise energetic arousal, reduce tense arousal, or affect both systems simultaneously.

The good news? Exercise serves to regulate exactly these functions. And going for a walk is accessible to many of our clients.

What I’ve Learned

I’ve done Walk+Talk for a few years and have learned that with all of the above noted benefits, there are clearly clients and sessions where Walk+Talk isn’t the best option. In general, I’ve learned that:

- Walk+Talk isn’t appropriate for everyone, and especially not to process trauma

- Location matters - pick a route that isn’t brimming with people

- Eye contact matters - I alternate Walk+Talk sessions with in-office sessions to be able to increase eye contact and to be able to access pscyho-education tools such as posters and handouts

- A discussion of the limits of confidentiality is crucial

The Take Away

Walk+Talk may be a great option for some of your clients who feel stuck, need a change, or who need to add some light exercise to the self-care routine and learn well by example. At the same time, there are limits to Walk+Talk—but the good news is that all of the above information is applicable to our clients—and to us! Being able to go for a walk or run before or after a work day can be a wonderful way to get unstuck with clients and tend to our own self-care and wellbeing.

References

- Profile of Mood States, McNair, Lorr & Droppleman, 1971, Morgan (1985b)

- Greist et al. (1979)

- Berger & MacKenzie, (1981).

- Hays, 1994, Jongsgard, 1989, Sime, (1996).

- Jongsgard, 1989

- Gauvunm Rejeski and Norris (1996)